There are numerous concepts of sound production, and I prefer avoiding conversations that debate "right" versus "wrong" concepts of ensemble sound production. Rather, I choose to respect a conductor's decision to approach his or her ensemble's sound in a certain manner, provided it is an appropriate quality for a particular composition and that the best interest of the music is served. I fondly remember my days as a high school and college student when I started listening to music in a more serious way, and thus began gaining greater appreciation for and insight into the many aspects of musical performance. As a trumpet player, my early listening habits tended to focus on instrumental ensembles including orchestras, brass quintets and wind bands. I was and continue to be an avid listener of classical music, and I recall eventually being able to differentiate the Chicago Symphony Orchestra under the baton of Sir Georg Solti from the Philadelphia Orchestra under Eugene Ormandy simply by listening to the unique quality of sound that each ensemble produced. The CSO, of course, had that marvelous brass sound, while Philadelphia possessed a rich, lush string sound. Both were truly world-class ensembles, but their sounds were quite distinct. The point is that conductors of any ensemble, through deliberate thought and careful decision-making, should arrive at their personal concept of sound, and teach toward that concept.

I know that my personal performance experiences as a trumpet player in the Texas Tech University Symphonic Band under the direction of James Sudduth and the University of Illinois Wind Symphony under James F. Keene significantly shaped my opinions about the ideal wind band sound. Like the conductors with whom I studied, I subscribe to the principle that the desired fundamental sound of a wind band is that which is a well-blended, dark, resonant sound that is built on the low sounding instruments within the band. Who has influenced your concept of band sound, and how has that influence affected the way you approach your ensemble's sound?

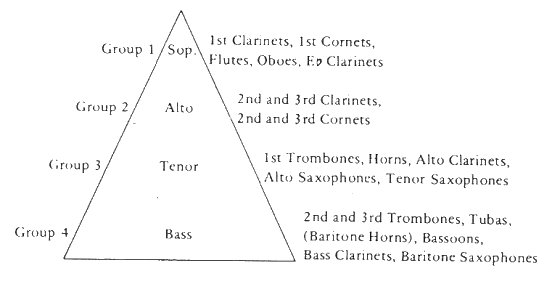

I assume that a large number of wind band conductors have come to know this approach to balance and ensemble sound production as the "pyramid system." This popular phrase resulted from the teachings and highly influential writings of Dr. Francis McBeth, especially his manual entitled Effective Performance of Band Music: Solutions to specific problems in the performance of 20th Century Band Music, I fully endorse the pyramid of sound concept for wind bands that has been championed by Francis McBeth for several decades now, and that concept essentially sets forth the idea that low voices in the band should contribute more sound to the full ensemble sound than the high voices.

To achieve a pyramid of balance, band members should think, listen, and balance down at the section, instrument family, and full ensemble levels. Ensemble members that play higher sounding instruments should fit their sound inside the sound of lower instruments. Special attention must always be given to inner voice parts or they will often fail to adequately contribute to the total band sound. It is important to constantly monitor for good balance within the band, but also to listen for proper blend, which results when students match volume, make a uniform quality of sound, and produce good intonation within sections and families of instruments. Good ensemble balance and blend are two essential components of achieving a satisfying band sound.

Conductors should teach their students what proper ensemble balance and blend sounds like and why good balance and blend enables bands to achieve a desired ensemble sound. With this in mind, it can be effective to first demonstrate improper balance by having your band invert the pyramid of sound creating a bright sound, or by having individual players "stick out" in certain sections to illustrate the effects of poor blend. Following this demonstration, you can provide the band some type of signal which indicates to them to increase the bass voices while decreasing the treble voices, gradually creating more of a pyramid of balance that will affect the sound in a most revealing and positive manner.

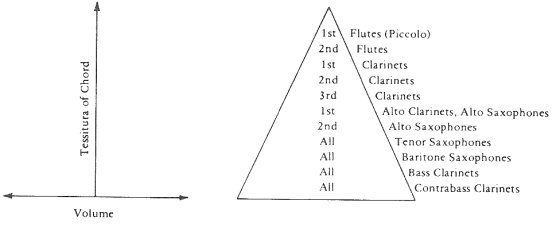

Dr. McBeth proposed that pyramids may be created on various levels from the full ensemble to instrument families to individual sections. The three diagrams below from Effective Performance of Band Music illustrate this approach:

Diagram 1: Full Ensemble Balance

Diagram 2: Woodwind Family Balance

Diagram 3: Brass Family Balance

Notice that within Diagrams 2 and 3, there are "double pyramids" which indicate the proper balance within each family and for each instrument section that commonly has multiple parts. See Effective Performance of Band Music by Francis McBeth for a more detailed explanation of the pyramid of balance concept.

Once the preferred fundamental sound concept has been established, a plan should be devised to enable the ensemble to develop that sound. The early phase of a rehearsal is the most logical time to work on sound development. It is important that an adequate amount of time be given to the "developmental" portion of the rehearsal, and additional time for this type of ensemble work should be afforded to younger ensembles. At the high school level, I typically dedicated 20- 25% of each rehearsal to fundamental work, which included refinement of sound, scales, articulation, intonation, technique, etc. With the Iowa Symphony Band, I use approximately 10 minutes out of a 90-minute rehearsal to establish the band's sound and tune the ensemble.

To begin, excellent playing fundamentals must be in place. These include a properly working instrument, exemplary posture, effective breathing, adequate airflow and the production of a characteristic tone by each individual member of the ensemble. In experiences with my own ensembles and as a guest conductor of honor bands, I find that I must frequently stress and reinforce the importance of excellent performance fundamentals. I believe most would agree that the success of an athlete, athletic team, musician or musical ensemble is largely dependent on the development and application of strong performance fundamentals. If I notice students sitting improperly during rehearsal or if the ensemble is not utilizing breath support to their fullest, I will quickly identify the problem and will make necessary adjustments. In fact, in recent years I have begun incorporating a few minutes of focused breathing exercises at the beginning of rehearsals. Such exercises serve to "warm up" the students' use of air and clear their minds so they can focus their attention on the rehearsal. I will reinforce the importance of breathing during the course of a rehearsal if I feel the ensemble is not fully utilizing breath support. The Breathing Gym by Sam Palafian and Patrick Sheridan provides some outstanding exercises to improve breath control and airflow, and these exercises can easily be applied to individual as well as large ensemble settings.

During the first part of the rehearsal, after greeting the students, I will typically have them stand as I lead them through a few breathing exercises, which I vary for each rehearsal. I will then have them perform some non-notational long tone exercises such as those that are commonly referred to as "Remington patterns," which begin on some predetermined unison pitch (often Concert F) and are performed in descending and/or ascending minor seconds in increasing intervals. The Remington pattern can also be applied effectively to chordal work. Additional non-notational exercises include major, minor and chromatic scales, scales in various intervals such as thirds, fourths, fifths, etc. and scales performed in a round by instrument group (Always start with the low voices! See Diagram 1 for group assignments) to name a few. These types of exercises will enable your students to focus their complete attention on their individual sound production as well as that of the entire ensemble. Incorporate singing to encourage the students to be active listeners and more completely engaged throughout this process. You may want to have them sing a note within a scale ("Sing the next note in the scale"), or a chord tone ("Sing your note within the chord." "Now, sing the tonic."). There are many techniques that can be implemented that will create variety for you and your students as well as enable them to develop important performance concepts. Refer to the end of this article for an illustration of the Remington pattern, which was extracted from an article by John P. Paynter, A Daily Warm-Up Routine, which appeared in the September/October 1984 issue of Band.

It is important to keenly monitor and assess the sound the ensemble is producing at all times. Tendencies are that, as the students perform at stronger dynamic levels or in higher tessituras, the quality of the sound will brighten. In establishing the base ensemble sound, it is essential to eliminate these performance tendencies, and achieve consistency in all ranges at all dynamic levels.

If you incorporate technical work such as scales, arpeggios, rhythm studies, etc. within your full ensemble rehearsals, the second phase of the developmental section of the rehearsal is an ideal time for that material. Remember to constantly monitor the band's use of air and sound production as they begin to perform more technically challenging material. This is exactly the time when young musicians may begin to back off on their breath support and thus start to produce poor, unsupported tones.

The culmination of this portion of the rehearsal, which is often referred to as the "warm up," should be the performance of a chorale or a slow, lyrical composition. Ensemble members should be given opportunities to apply developmental concepts such as tone production, balance, blend, phrasing, dynamics, etc. within a musical context. To create some variety in this part of the rehearsal, I will often have the woodwinds play or sing their parts while the brass buzz their parts of the chorale on their mouthpieces in order to open up their sound and to work on their listening skills. If I find the band's attention lacking, I will often have them (a) sing the chorale to become more aware of intonation, (b) transpose the chorale up or down a given interval to increase their focus, (c) "bop" (perform all notes in short rhythmic values) the chorale to illustrate precision problems or the importance of some inner part movement, and/or (d) slur the entire chorale to improve airflow and phrasing.

There are many outstanding collections of chorales available for concert bands at every performance level. I have enjoyed using Sound Training: Twenty-Six Chorales of J. S. Bach, arranged by Wayne Gorder, published by Ludwig Music, for my chorale work with the Iowa Symphony Band. Of course, the Sixteen Chorales by Johann Sebastian Bach, arranged by Mayhew Lake is an excellent, time-tested collection of chorales. These are but two of many fine chorale books that are now available for bands of any ability level.

Instead of utilizing a chorale at the end of the developmental portion of the rehearsal, you may want to have the band perform a slow, lyrical work or selected passages from that work. Compositions such as Salvation Is Created by Tchesnokov, Nimrod from Enigma Variations by Elgar, Come, Sweet Death by Bach/Reed, Amazing Grace by Himes or Ticheli, Shenandoah or Loch Lomond by Ticheli, Llwyn Onn by Hogg, Ave Maria by Biebl, Air for Band by Erickson, etc. work beautifully during this part of the rehearsal. It is through the performance of slow, sustained music that students have the best opportunity to refine their sound production as well as their overall musicianship.

Once the first phase of the rehearsal has been completed, the ensemble is ready to begin work on their current concert repertoire. However, the developmental work must continue. As the band performs various passages within compositions, they should ultimately apply the concepts introduced and reinforced at the beginning of the rehearsal. Be sure you assess their sound production throughout the entire rehearsal, along with their articulation, intonation, phrasing, dynamic contrast, etc., and make corrective or reinforcing comments as needed. We should never accept a sound that is a poorer quality than the most focused, beautiful tone which they are capable of producing.

Remember, our students can usually very quickly replicate a performance concept if they simply have an adequate model. So, thanks to an increasing availability of recordings of outstanding bands at all age/ability levels, it is possible to obtain representative concert band performances that will clearly illustrate your preferred concept of ensemble sound for your middle school, high school or collegiate students. You might already use this method when demonstrating the desired tone qualities of individual instruments, but it is also a powerful way to model the quality of the full ensemble sound.

Additionally, it is helpful to frequently record your band not only for your own assessment purposes but also to enable your students to listen to and evaluate their sound as an ensemble. Involve your students in the assessment process and have them identify the strengths and areas of weakness they hear within their own band. What do they like about the sound they make? What do they not like about their sound? What can they improve? How can they improve it?

At this time, it is important to note that a "one sound fits all" approach to ensemble sound should be avoided. The fundamental band sound is one that is developed according to the principles previously outlined; however, conductors, through score study and interpretation, must derive at a quality of sound that is appropriate for each individual composition they are conducting with their ensembles. Some compositions or sections within a work may require a dark, rich quality of sound from the ensemble while others may need a bright, edgy sound. It is possible that a piece will require a sound that results from balancing the band according to figure 2, similar to an hourglass, or perhaps the appropriate balance for a work would more appropriately resemble a diamond structure shown in figure 3. Wind band compositions that have been written within the past few decades have grown increasingly sophisticated on many musical levels, thus compelling conductors to give adequate attention to the quality of sound that may be required of each unique work. The standard pyramid of balance, figure 1, may be appropriate in the majority of musical situations, but not all of them. Conductors must have the knowledge, creativity and confidence to understand when a change is needed in the band's sound and what adjustments to make to create the appropriate sound.

1. |

2. |

3. |

4. |

And finally, it is often easy to overlook the contributions of the percussion section as we focus on the sound production and balance within the band's wind sections. However, the quality of sound a percussion instrument or section contributes to a work can affect the overall ensemble sound as much as that of a wind instrument or section. Again, from experiences with my own ensembles and as a guest conductor, I find that percussionists tend to favor articulate, dry sounds produced by hard mallets or sharp, crisp performance techniques. Similar to my personal sound preferences of the wind instruments, I generally prefer percussion sounds that are dark and resonant rather than those that are bright and brittle. Of course, changes must be made in accordance with the musical context, but I prefer making adjustments from a position of the initial sounds being dark and resonant, rather than from the other direction. Take care to attend to the sounds the percussion section is delivering. Young players especially seem to be content if they strike the proper instrument at the proper time, but they often neglect to consider the quality of the sound they produce. And remember, the quality of a percussion sound can be changed greatly simply by changing the performance technique. It is not always necessary to start by changing a stick or mallet. Describe the sound you want and see how close your students can get to that sound by making their own performance decisions!

The sounds that our bands produce should be of primary importance to all of us, and we must take steps to aptly describe the desired quality of ensemble sound as well as nurture that sound in a careful, consistent manner. My advice is that you establish a sound routine (Pun intended!) through which you work each day to develop the sound of your band, but take care to create variety within that routine so that your students do not become bored or complacent with this very important part of the rehearsal. Be patient. Like music itself, the development of an ensemble's sound is an on-going endeavor, and although we conductors may eventually be satisfied with the quality of sound our band is achieving, there will always be room for refinement.

References:

Chodoroff, Arthur. Performance: Ensemble Sound. In

School Band and Orchestra, December

2010. Lowell, MA: Symphony Publications, 14-16.

Gorder, Wayne. Sound Training: Twenty-Six Chorales

of J. S. Bach. Cleveland, OH: Ludwig

Music Publishing Co., 1995.

Lisk, Edward. The Creative Director: Alternative

Rehearsal Techniques. Ft. Lauderdale, FL:

Meredith Music Publications, 1987.

McBeth, Francis. Effective Performance of Band

Music: Solutions to specific problems in the

performance of 20th Century Band Music. San

Antonio, TX: Southern Music Co., 1972.

Paynter, John. A Daily Warm-Up Routine. In Band,

Volume 1, Number 1. Traverse City, MI:

Band, Inc., 1984, 6-9.

Williamson, John. Rehearsing the Band. Cloudcroft,

NM: Neidig Services, 1998.

(From A Daily Warm-Up Routine by John P. Paynter.

September/October 1984 issue of BAND.)

Richard Mark Heidel is director of bands in the School of Music at The University of Iowa where he conducts the Symphony Band, teaches graduate courses in conducting and band literature, guides the graduate band conducting program, and oversees all aspects of the University of Iowa band program. Ensembles under Dr. Heidel's direction have performed at national, regional and state conferences including those of the College Band Directors National Association, National Association for Music Education, Iowa Bandmasters Association, Wisconsin Music Educators Association, Illinois Music Educators Association and National Band Association-Wisconsin Chapter. He has also led concert tours to Ireland and England as well as throughout the Midwest. Reprinted with permission from the Winter 2010 issue of the Iowa Bandmaster.