|

Teaching the Art of the Shift in Orchestra Class

The ability to shift and play in positions can catapult a beginning

orchestra program, almost immediately, into an intermediate

ensemble by that simple skill alone. The ability to shift extends the

range on each string including the upper string, which then

broadens the available repertoire. It often eliminates awkward string

crossings and/or fingerings, avoids objectionable open strings or

long notes on weak fingers, facilitates vibrato, and provides multiple

opportunities for expressivity.

Now, we need to teach shifting to thirty or forty youngsters all at the same time. Or perhaps we want to provide guidance for better accuracy, smoothness and expressive qualities for our more advanced high school students. Even for a native string player this might seem a daunting task. The following are graduated tips and suggestions for motivated teachers who understand the possibilities and efficacy for an orchestra program which is engaged in the art of the shift. When do we start to teach shifting? The answer is: almost immediately. That is, when we first teach and insist upon acceptable posture with our beginning students including a well set up left hand position. Checking left hand position for future success includes making sure the forearm is connected to the base of the palm in a relative straight line. For upper strings the elbow goes under the instrument; for the lower instruments the elbow points away from the instrument. For upper strings the thumb is placed on the neck of the instrument in a relaxed convex curve opposite the 1st and 2nd fingers. For lower strings, the thumb is centered in a relaxed convex curve under the neck opposing the 2nd and 3rd fingers. The final test of a well-positioned left hand is when the fingers are relaxed and curved, they fall on a middle string in a relative straight line.

Fingers, relaxed and curved, above the strings When teachers insist on appropriate posture they make the future shift possible. When they don't insist, they make the future shift much more difficult! Youthful players often express four objections or difficulties in shifting:

The Rolland Shuttle - Violin

The Rolland Shuttle - Cello

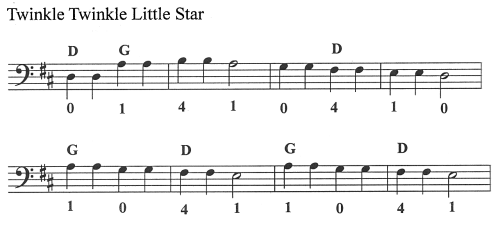

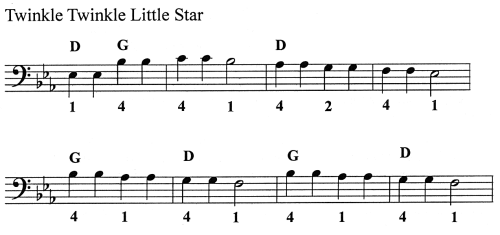

B. Paul Rolland1 and Loretta McNulty2 and others recommend the use of the 8va harmonic—a positive variant! The "Shuttle" exercise can be effectively used in warm-up beginning with the first days of instruction through the most advanced orchestra program. C. Place a small piece of toilet paper, tissue or small cloth between the finger and the fingerboard then simply slide up and down on a middle string. Youthful students somehow find this exercise entertaining, yet, like the "Shuttle," this movement shapes the left hand, correctly places the elbow, moves the hand as a unit, and frees the "sticky" feeling. D. Left hand thumb games are always in order. A small piece of sponge placed between the thumb and neck can help younger students get the idea of a "soft thumb." Tapping and rubbing the side of the neck are early exercises quickly done, often overlooked, yet essential to future development. More advanced students can play a phrase or line of music taking the thumb completely off neck of the instrument. The student soon finds a relaxed, more natural, thumb position that releases the tension in both the thumb and left hand. E. Mental pictures are always important for youngsters. Try this: pretend that you are in a swimming pool shoulder deep in water—relax the arms. They will float to the surface. That is how you want the arms to feel when set up correctly. I used what I called the "Flab Technique" for some time. Without an instrument, I demonstrated flipping the relaxed flab on both my forearm and upper arm and told my students that is how you want your arms to feel—not clenched or tight. This worked for a while until one young fourth grader said with plaintive eyes, "But Dr. Tom, I don't have any flab." You may have your own visuals—something to do with Jell-O or perhaps with Neil Armstrong and weightless space, but whatever story you concoct, it is important pedagogically to give youngsters something they can visualize. F. Students from second year through high school can learn a scale on one string beginning on the first finger or using first finger alone. Or, try Au Clare de la Lune, Mary Had A Little Lamb or some other simple linear melody on one string and first finger only. Make sure students keep all their fingers lined up with the string. G. Play Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star in each key going up the fingerboard chromatically or in the key of the literature placed in front of the students. It is a pattern, so have them figure out the fingering starting on an open string, and then starting on first finger. The basses may need some assistance with fingering—see below.

H. I used The Blob for a number of years in string orchestra warm ups. One reader asked: "Did you use The Blob during the entire school year?" Well, yes, certainly not every day. I did vary it. I inserted slurs, played it in rhythms (a particularly difficult ensemble rhythm or even cross rhythms in our selected repertoire), used different bowings including Martelé, Marcato, Spiccato, Staccato, as well as simple Détaché, and bow placement including Sul ponticello and Sul tasto. Variation was key to have students buy into the repetition. (The Blob was published in Spring 2013 Issue of CMEA Magazine. Overall, the most important factor in students learning to shift is the persistence of the teacher in working on this technique and finding ways to keep it fresh and fun. More expressive shifting possibilities include portamento, shifting with the finger on the string or shifting with the finger in the new position for different affects. Perhaps with some suggested shifting practice techniques included as well. 1Basic Principles of Violin Playing, Paul Rolland. Music Educators National Conference, 1959. P. 23. 2 Setting the Stage for Shifting, Loretta JW McNulty. Lecture given at the California All-State Music Education Conference, 23 February 2013. Loretta teaches in the Lafayette and Mt. Diablo school districts and was Bay Section CMEA Outstanding Orchestra Director for 2013.

Dr. Tatton is a retired string specialist with the Lincoln Unified

School District in Stockton, California. His previous positions

include Associate Professor of String Education, Music History,

Violist in Residence and Director of Orchestras at both Whittier

College and the University of the Pacific. His monograph on public

school string teaching, Connecting the Dots, was published in

2003. He is currently active as a clinician and adjudicator as well

as making appearances at school in-service training conferences.

He is also the previous CMEA Orchestra Representative.

Return to top |

|