|

Successful Interdisciplinary Communication in Schools: Understanding Important Special Education Concepts and Initiatives

Reprinted from volume 5 no. 1, pp 29-37 of Imagine, the early childhood online magazine published by de la visa publisher

Editor's note: Although this article was written for another population, the ideas are relevant for music educators and applicable at all levels and in all areas of school music.

Successful interdisciplinary communication requires that stakeholders

not only have knowledge of their own disciplines, but a clear

understanding of their colleagues' disciplines as well. Music therapists

often work in education settings, primarily with students who receive

special education services, which makes special educators one of their

closest allies. Consequently, it is important for music therapists to

understand concepts and initiatives in the field of special education, as

well as to know and use the associated appropriate terminology when

communicating with IEP team members, parents, and school or site

administrators. While much of the following information mainly pertains

to school settings and children above the age of five, it is important for

music therapists, and music educators, to understand issues that young

children and their families will face in the child's next educational

environment.

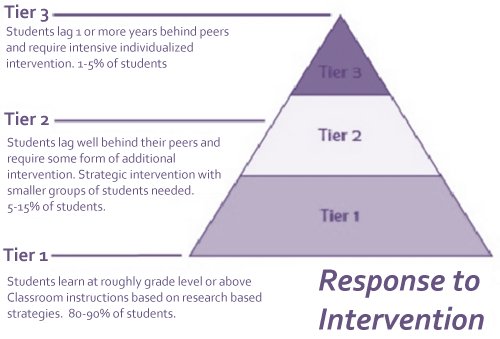

A shared core vocabulary is helpful in establishing a common framework through which music therapists, music educators, early interventionists, and special educators can best meet the needs of children with disabilities. Being able to converse about current topics in special education also demonstrates professional awareness, an understanding of recent developments in the field, and a willingness to work collaboratively with other professionals. A number of initiatives in special education have occurred over the past 15 years, with some being mandated by amendments to the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. Having a working knowledge of these current perspectives in special education is necessary for music teachers and therapists to have informed discussions with colleagues and to participate more fully in IEP meetings. Some initiatives in special education, or certain elements of initiatives, are already a part of music therapy practice, though terms may be identified by different names. Knowing what elements of special education and music therapy practices are shared or different, allows for more consistent and coordinated efforts on behalf of students with disabilities. Following are brief reflections on and summaries of special education concepts for music educators and therapists working in schools who would like a basic understanding of these important initiatives. We present below brief summaries for five special education concepts for music therapists as well as music educators who would like a basic understanding of these important initiatives. We begin with one in arts education that is closely aligned with the Common Core State Standards and the National Core Arts Standards. National Core Arts Standards (NCAS) Most educators are aware of the Common Core State Standards www.corestandards.org (CCSS) for Math and English Language Arts. This national initiative describes what students should know in these content areas at the completion of specific grade levels. The purpose of the Common Core initiative is to establish consistent educational benchmarks for all states, and to ensure that students graduating from high school are prepared for the next level of educational experiences. The majority of the states have adopted these voluntary standards, while a few states have chosen not to adopt the national standards. The National Core Arts Standards nationalartsstandards.org (NCAS) is a new initiative established in June, 2014 to provide a platform for excellence in delivery and outcomes of arts education in PreK-12 education. Music, Visual Art, Dance, Theater and Media Arts are included in the standards document. These voluntary arts standards are designed to promote thinking, learning and creating as processes of arts education. The standards provide comprehensive expectations and equitable opportunities for all students. Experts in arts in special education assisted the development team to ensure that the standards were written in an inclusive manner with opportunities for success at varied levels of abilities. This conceptual framework for arts learning is based on philosophical foundations and lifelong goals related to 1) the arts as communication, 2) the arts as creative and personal realization, 3) the arts as culture, history and connectors, 4) the arts as means to well-being, and 5) the arts as community engagement. Based on this foundation, artistic literacy is developed through the artistic processes of creating, responding, performing/presenting/producing (based on the art form), and connecting. Anchor standards and Performance standards describe the general knowledge and skills that students are expected to demonstrate as evidence of their artistic literacy, both generally across the arts and in discipline specific language. Measurable learning goals are created through grade level achievement outcomes PK-8, and through proficiency levels in high school (proficient, accomplished, and advanced) (NCCAS, 2013). Breaking down the framework into various creative practices, we find strategies that are frequently utilized by music therapists in a variety of age and ability settings. These creative practices from the standards include 'imagine,' 'investigate,' 'construct,' and 'reflect.' Using developmentally appropriate practices, music therapists and teachers provide opportunities for students to create an image (imagine), observe and explore (investigate), create something new (construct) and discuss or think about outcomes (reflect). Combining these practices with Universal Design for Learning practices, the arts standards can be accessible to students of varying ability levels in inclusive settings as well as individualized or small group arts experiences (Malley, 2013). The National Core Arts Standards were developed to provide a foundation for balanced education through arts experiences. Teachers, specialists and administrators can use the standards to develop curriculum for success as informed students of the arts as well as educated and contributing members of society. Engagement in the arts can prepare students for better outcomes in school, career and engagement with others in the community. Response to Intervention (RTI) Response to Intervention (RtI) is a multi-tier, school-wide approach for the early identification and support of students with learning and behavior needs. This systematic, data-based approach provides a structure to assess needs of students and to implement additional support to improve learning and behavioral outcomes. Using RtI, all students are screened to determine their progress on specific benchmarks, and students who are not meeting benchmarks are identified for additional support to remediate learning and behavior deficiencies. Ongoing assessments continue to inform decisions about how to best support the students' learning (Batsche, 2006; Brown-Chidsey & Steege, 2010; Reynolds & Shaywitz, 2009). School-wide teams create the foundation for the decision-making process, with specific teams responsible for navigating the process, evaluation, and instructional support. The team members identify the problem that the student is having, determine why it is happening, implement a process to remediate the student's deficiencies, and then evaluate the student's outcomes. Classroom teachers, administrators, support staff and related service providers are involved in the team decision-making process (Glover & DiPerna, 2007; McCook, 2006). RtI consists of a three-tier system of interventions (see Figure 1). Tier 1 is where all children receive core instruction in literacy and math. Approximately 80% of students will respond very well to the core instruction, achieve proficiency and have their learning needs met at this level. Tier 1 provides differentiated and flexible group learning experiences within the general education classroom, with at least 90 minutes per day devoted to literacy and 60 minutes per day for math. Tier 2 is focused on approximately 5-10% of the students who will need supplemental interventions in addition to the core instruction to help them make progress. In addition to Tier 1 instruction, students in this level receive a minimum of 30 minutes per day of small group instruction. Approximately 1-5% of the most deficient students may need the intensive support of Tier 3. These students need instruction that is significantly different than the core instruction, which includes additional small group instruction plus Tier 1 and 2 experiences. Progress monitoring occurs throughout to determine if the students are advancing or if instructional strategies need to be changed (Kovaleski, 2007; Whitten, Esteves & Woodrow, 2009). Music can be used to provide extra support needed by some students. Music researchers have investigated many topics related to literacy, such as music learning to improve reading, music embedded into the curriculum to enhance reading skills, music to develop auditory discrimination skills, and contingent music to promote reading behaviors (Darrow et al., 2009; Gromko, 2005; Humpal & Colwell, 2006; Lamb & Gregory, 1993; Pane & Salmon, 2011; Register, 2001; Register, Darrow, Standley & Swedberg, 2007; Salmon, 2010; Telesco, 2010; Wolfe & Noguchi, 2009). Results from a meta-analysis focused on music to improve learning (Standley, 2008) indicate that the benefits are greatest for early intervention programs, students identified with learning difficulties benefit more than typically developing students, and contingent music can be effective to reinforce reading behaviors. Studies showing the best outcomes used music as a contingency, music as a cue for attention, or had reading tasks embedded into music concepts. So how does music education/therapy fit in to the RtI approach? With RtI, schools have a way to provide additional support to students without requiring that students qualify for special education services. Music therapists along with other related services providers are typically part of the RtI teams and can create specialized, research-based interventions for students who respond well to music. Students in Tiers 2 and 3 may be able to benefit from the addition of music therapy services to promote learning and positive behavioral outcomes in a general education environment.

Most music teachers and therapists will report that managing students with challenging behaviors is the greatest barrier to effective classroom instruction. Even though music is a highly desirable activity for most students, music educators have indicated that students with behavior disorders are the most difficult to manage in the inclusive music classroom. They typically exhibit unacceptable patterns of behavior, are nonconforming to the norms of the classroom, and often make the learning environment unproductive for others. These students, like many students with disabilities, require instructional interventions to manage their disability and to assist them in becoming educated and sociable adults. Positive Behavioral Support (PBS) is a special education initiative that has been particularly beneficial for these students. The purpose of Positive Behavioral Support (PBS) is to create a supportive and successful environment for all students, though particularly for those with the most challenging behaviors. It refers to a range of preventive and positive interventions designed to eliminate problematic behaviors and to replace them with behaviors that are conducive to academic and social success. PBS is also a comprehensive research-based approach intended to address all aspects of a problem behavior. It involves a proactive, collaborative, assessment-based process to develop effective and individualized interventions to discourage challenging behaviors (Shepherd, 2010). Professionals employing PBS are equally committed to teaching and reinforcing pro-social behaviors (Sailor, Dunlap, Sugai, Horner, 2009).

Along with reducing problem behaviors and teaching desired behaviors, the PBS approach is structured to address plans for a student's future. It is an approach that merges values regarding the rights of people with disabilities with practical application of how learning and behavioral change occur. The principal goal of PBS is to improve the daily lives of students and their support providers in home, school, and community settings (Hallahan, Kaufman, & Pullen, 2009; Turnbull, Turnbull, Wehmeyer, & Shogren, 2013). PBS is supported by recent mandates, including the 1997 amendments to the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, which call for the use of functional behavioral assessments and positive supports and strategies (IDEA, 2004). Self-Determination Individuals who are in control of their lives, those who make sound decisions, solve problems, set attainable goals for themselves, and regulate their behavior are viewed positively by most cultures. They are considered to be self-determined individuals. These are volitional acts on the part of an individual to maintain or improve his or her quality of life. Ryan and Deci (2000) are most closely associated with self-determination theory. They propose that self-determination encompasses three innate psychological needs—competence (feeling a sense of achievement), autonomy (feeling in control), and relatedness (feeling safe and secure with other people). They postulate that these needs, when satisfied, can lead to self-motivation, physical and emotional well-being and, if not satisfied, can lead to physical and even mental illness. Research documents positive outcomes for children with disabilities who have learned skills related to self-determination—positive outcomes for their social development, academic development, and well-being. Although many children learn to become more independent and acquire the knowledge and skills associated with self-determination implicitly, other children require more guidance and instruction. Providing for self- determination is essential for successful transition in school and throughout life, but can it be taught? The concept of self-determination in the psychological literature and subsequent research led to the development of definitions, strategies and the development of specialized published curricula. Wehmeyer is cited frequently for his work promoting self-determined behavior in children with intellectual and developmental disabilities. For purposes of education and rehabilitation, he states that "self-determination is 1) best defined in relationship to characteristics of a person's behavior; 2) viewed as an educational outcome; and 3) achieved through lifelong learning, opportunities and experiences" (Wehmeyer, 1996). Music therapists can make appropriate transfers to their settings for young children from his curriculum, The Self-determined Model of Instruction (Wehmeyer, Palmer, Agran, Mithaug, & Martin, 2000). Palmer and colleagues (2014) and others (e.g., Brotherson & Weigel, 2008; Erwin & Brown, 2003; Shogren & Turnbull, 2006) provide strong arguments for nurturing self-determination early in life and stress the importance of family-teacher partnerships working together for meaningful outcomes across early childhood settings and homes. When included in the curricula, Palmer and her colleagues caution that "it would be developmentally inappropriate for preschool-age children to be expected to exercise independent choices, decisions, and problem solving as self-determination is defined for adolescents and young adults (p. 39)." They propose a Self-Determination Foundations model with three interactive critical components as foundations for the later development of self-determination for young children with disabilities: a) child opportunities for expressing and making choices or engaging in simple problem solving, b) self-regulation, and c) engagement. Although many music therapists may incorporate skills associated with self-determination into their sessions with young children, no doubt children will benefit from more opportunities to learn and practice these skills. Introducing choices to students, teaching them how to self- regulate (set goals and reach them), giving them increasingly more autonomy, honoring their preferences, giving them problems to solve within their capacity and strategies to solve them, and providing opportunities for them to experience individual achievement require therapists to be aware of the short- and long-term consequences of students' actions and to make students aware of these consequences as well. Children of all ages and with varying capabilities can learn what questions to ask themselves and what actions to take to accomplish their goals (i.e., academic, social or music). Differentiated Instruction (DI) Young children come to music sessions, and students later come to the music classroom with different educational readiness, learning styles, abilities, and preferences. In addition to these learner differences, classrooms in the United States are becoming more linguistically and culturally diverse each year. Differentiated instruction (DI) is an approach to teaching and learning that allows for these individual differences. Thousand, Villa, and Nevin (2007, p. 9) define differentiated instruction as "a process where educators vary the learning activities, content demands, modes of assessment, and the classroom environment to meet the needs and to support the growth of each child." Various accommodations and adaptations are also included as a part of the instructional process. Working with individual children, as music therapists and teachers often do, is not the same as differentiated instruction. Differentiated instruction involves working with groups of students, and individualizing the curriculum for those within the group. It shares many of the Universal Design for Learning (UDL) goals for teaching and promoting student learning, with both initiatives established to embrace student differences and to ensure students have every opportunity to learn in ways that best suit their individual needs. Both UDL and DI include built-in supports for students and suggest scaffolding instruction. However, DI differs from UDL in how and when instructional adjustments are made for students. DI makes use of formative assessments with accompanying adjustments in the curriculum. Tomlinson (2001) identified three elements of the curriculum that can be differentiated: content, process, and products. In brief, curriculum content should be aligned with learning goals and objectives, and the same for all students, with its complexity varied based on students' abilities to comprehend the material. Content delivery is varied, based on groupings that are flexible and fluid, and beneficial to both students and teachers. In differentiated instruction, formative assessments are a key feature, and are used to direct the curriculum. Formative assessments are used to evaluate students' readiness to learn and acquire knowledge. DI operates under the assumption that not all accommodations for learner differences can be planned proactively. Instruction should be fluid and variable, depending on the changing needs of the learners. A layered curriculum is one of the most salient features of DI. While the focus of the subject matter—the essential concepts—is the same for all students, individual students are learning the curriculum content at different levels of complexity, and are expressing what they know at different levels of sophistication. Giangreco, Cloninger, and Iverson (1993) suggested four levels of curriculum design: same, multilevel, curriculum overlapping, and alternative. In the first level, students are taught the same curriculum with only minor changes in the amount to learn or the time to learn it. In the second level, students are involved in the same curriculum with the same goal, but have different learning objectives based on subject matter complexity. In the third level, students are engaged in the same lessons, but the overall goal for learning the material may be different, such as social versus academic. In the final level, alternative, students' goals may be unrelated to those of their peers. The learner goals, objectives and curriculum content are appropriate alternatives that are more suited to the needs of the individual student. An example might be a student who is involved in a vocational training program while peers are given a more traditional academic curriculum. Another important component of DI is varying the instructional process, which is similar to the UDL principle of providing multiple means of representation. Ways of varying the instructional process is using multiple instructional formats, strategies, environments, as well as varying student and teacher configurations (Thousand, Villa, & Nevin, 2007). A final important component of DI is varying the expected products or outcomes of learning. Similar to the UDL principle of allowing for multiple and flexible expressions of student learning, this component of DI allows students to choose among options, or to design their own method of demonstrating what they know. Having varied methods of learner assessments in the same classroom also necessitates assigning multiple criteria for mastery of the curriculum content. While DI and UDL share several important principles for learning, the distinguishing feature of DI is less emphasis on proactive instructional design in favor of a formative instructional design based on student learning. Universal Design for Learning (UDL) The concept of a universal approach in education comes from the concept of universal design practices in architecture and products. As common needs of people with disabilities were gradually being met through accessible designs, these designs proved beneficial to everyone (e.g., curb cuts; lights controlled by a simple touch; lever handles for doors and sink faucets). Universal design is now required in IDEA, specific to the assessments of students. Inclusion in the law led to the development of educational practices, support, and the provision of resources for teachers (see the National Center on Universal Design for Learning). There are similarities in the overall concept related to architecture and education (UDL) as seen in the two definitions below:

Three primary principles provide a framework for UDL; principles were derived from stringent reviews of research evidence from different fields and are applicable for individual or group sessions in early childhood. A list of UDL principles with applications for young children from Conn- Powers and colleagues (2006) follows:

References

Batsche, G. (2006). Response to intervention. Alexandria, VA: National

Association of State Directors of Special Education.

Brotherson, M. J., Cook, C. C., Erwin, E. J., & Weigel, C. J. (2008).

Understanding self-determination and families of young children with

disabilities in home environments. Journal of Early Intervention, 31, 22-43.

Brown-Chidsey, R., & Steege, M. W. (2010). Response to Intervention.

New York: Guilford Press.

CAST (2011). Universal Design for Learning Guidelines version 2.0.

Wakefield, MA: Author. Center for Universal Design (CUD). Retrieved

from http://www.design.ncsu.edu/cud/

Conn-Powers, M., Cross, A., Traub, E., & Hutter- Pishgahi, L. (2006).

The universal design of early education: Moving forward for all children.

Beyond the Journal, Young Children, September 2006. Retrieved from

http://www.journal.naeyc.org/btj/200609/

Darragh, J. (2007). Universal design for early childhood: Access and

equity for all. Early Childhood Education Journal, 35(2), 1676-171.

Darrow, A., Cassidy, J., Flowers, P., Register, D., Sims, W., Standley,

J., Menard, E., & Swedberg, O. (2009). Enhancing literacy in the second

grade: Five related studies using the Register Music/Reading Curriculum.

Update: Applications of Research in Music Education, 27, 12-26.

Erwin, E. J., & Brown, F. (2003). From theory to practice: A contextual

framework for understanding self- determination in early childhood

environments. Infants & Young Children, 16(1), 77-87.

Giangreco, M., Cloninger, C., & Iverson, V. (1993). Choosing options and

accommodations for children (COACH): A guide to planning inclusive

education. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes.

Glover, T. A., & DiPerna, J. C. (2007). Service delivery for response to

intervention: Core components and directions for future research. School

Psychology Review, 36(4), 526-540.

Gromko, J. (2005). The effect of music instruction on phonemic

awareness in beginning readers. Journal of Research in Music

Education, 53, 199-209.

Hallahan, D. P., Kaufman, J. M., & Pullen, P. C. (2009). Exceptional

Learners: An Introduction to Special Education. Boston, MA:

Pearson/Allyn & Bacon.

Humpal, M., & Colwell, C. (2006). Early Childhood and School Age

Educational Settings: Using Music to Maximize Learning. Silver Spring,

MD: American Music Therapy Association.

IDEA (2004). Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act of

2004. Retrieved from http://idea.ed.gov/download/statute.html.

Kovaleski, J. F. (2007). Response to intervention: Considerations for

research and systems change. School Psychology Review, 36(4), 638-

646.

Lamb, S. & Gregory, A. (1993). The relationship between music and

reading in beginning readers. Educational Psychology, 13, 1.

McCook, J. E. (2006). The RtI guide: Developing and Implementing a

Model in Your Schools. Horsham, PA: LRP Publications.

Malley, S. (2013). Students With Disabilities and Core Arts Standards:

Guidelines for Teachers. Washington, DC: John F. Kennedy Center for

the Performing Arts.

http://nccas.wikispaces.com/Students+with+Disabilities+and+ Arts+Standards

NCCAS (2013). National Core Arts Standards: A Conceptual Framework

for Arts Learning. Retrieved from

http://nccas.wikispaces.com/Conceptual+Framework.

Palmer, S. B., Summers, J. A., Brotherson, M. J., Erwin, E. J., Maude,

S. P., Stroup-Rentier, V., Wu, H. Y., Peck, N. F., Weigel, C. J., Chiu, S.

Y., McGrath, G. S., & Haines, S. J. (2014). Foundations for self-

determination in early childhood: An inclusive model for children with

disabilities. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 34(1), 38-47.

Pane, D. & Salmon, A. (2011). Author's camp: Facilitating literacy

learning through music. Journal of Reading Education, 36, 36-42.

Register, D. (2001). The effects of an early intervention music curriculum

on pre-reading/writing. Journal of Music Therapy, 38, 239-248.

Register, D., Darrow, A., Standley, J., & Swedberg, O. (2007). The use

of music to enhance reading skills of second grade students and student

with reading disabilities. Journal of Music Therapy, 44, 23-37.

Reynolds, C. R., & Shaywitz, S. E. (2009). Response to intervention:

Ready or not? Or, from wait-to-fail to watch-them-fail. School Psychology

Quarterly, 24(2), 130-145.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the

facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being.

American Psychologist, 55, 68-78.

Sailor, W., Dunlap, G., Sugai, G., & Horner, R. (2008). Handbook of

Positive Behavior Support. New York, NY: Springer.

Salmon, A. (2010). Using music to promote children's thinking and

enhance their literacy development. Early Child Development and Care,

180, 937-945.

Shogren, K., & Turnbull, A. (2006). Promoting self- determination in

young children with disabilities: The critical role of families. Infants &

Young Children, 19, 338-352.

Shepherd, T. L. (2010). Working With Students With Emotional and

Behavior Disorders: Characteristics And Teaching Strategies. Upper

Saddle River, N.J.:Merrill.

Standley, J. (2008). Does music instruction help children learn to read?

Update: Applications of Research in Music Education, 27, 17-32.

Telesco, P. (2010). Music and early literacy. Forum on Public Policy, no.

5. Retrieved from

http://ecrp.uiuc.edu/v10n1/bolduc.html.

Thousand, J., Villa, R., & Nevin, A. (2007). Differentiated Instruction:

Collaborative Planning and Teaching for Universally Designed Lessons.

Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Tomlinson, C. (2001). How To Differentiate Instruction In Mixed-Ability

Classrooms (2nd ed.). Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and

Curriculum Development.

Turnbull, A.P., Turnbull, H.R., Wehmeyer, M.L., & Shogren, K. (2013).

Exceptional Lives: Special Education in Today's Schools (7th ed.). Upper

Saddle River, NJ: Merrill/Prentice Hall.

Wehmeyer, M. L. (1996). Self-determination as an educational outcome:

Why it is important to children, youth, and adults with disabilities. In D.

Sands & M. Wehmeyer (Eds.). Self-Determination Across the Lifespan:

Independence and Choice for People With Disabilities (pp. 17-36).

Baltimore: Brooks.

Wehmeyer, M. L., Palmer, S. B., Agran, M., Mithaug, D. E., & Martin, J.

E. (2000). Promoting causal agency: The self-determined model of

instruction. Exceptional Children, 66, 439-453.

Whitten, E., Esteves, K., & Woodrow, A. (2009). RTI Success.

Minneapolis, MN: Free Spirit Publishing, Inc. RTI Action Network.

Retrieved from http://rtinetwork.org.

Wolfe, D., & Noguchi, L. (2009). The use of music with young children to

improve sustained attention during a vigilance task in the presence of

auditory distractions. Journal of Music Therapy, 46, 69-82.

Return to top |

|